The Irish are largely Catholic – that’s common knowledge. But weren’t they previously ‘pagan’ Celts? How and when did Christianity actually find its way to this remote, green island in the Atlantic?

Page Contents (click line to jump the text)

Intro

Ireland is teeming with churches, cathedrals and monasteries. They can be found in every village and town, but also somewhere in the middle of nowhere in the countryside. For this reason, and because Christianity still occupies a very special place in Ireland’s history today, let’s take a closer look in this article:

Pre-Christian Ireland was deeply influenced by Celtic religion and Druidism. This belief system was quite complex and included a whole range of different deities and nature spirits.

The druids were familiar with this complexity. They acted not only as religious leaders, but also as judges, healers, poets and keepers of cultural knowledge. However, they only passed on their extensive teachings orally, which unfortunately limits our current knowledge of this period mainly to archaeological finds and later Christian records.

The Celtic year was characterised by important festivals such as Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane and Lughnasadh, which determined the agricultural cycle. Sacred sites such as springs, mounds and forests played a central role in religious life, and many of these sites were later adopted and reinterpreted by Christian missionaries.

The social structure was divided into two parts: There were the secular rulers, the clan chiefs and kings on the one hand and the spiritual-religious druids, who also acted as advisors to the clan chiefs and kings.

The latter was similar in the Christian world, as the powerful nobles and kings were advised by bishops and required the legitimisation and approval of the church, or even the Pope in Rome, for many decisions.

First Christian influences in Ireland

Even before the arrival of St Patrick, there was evidence of Christian influence in Ireland, mainly through trade relations and Romano-British contacts. The first Christian missionary known by name was Palladius, who was sent by Pope Caelestine I as a bishop to the ‘Irish believers in Christ’ in 431 – clear evidence of the existence of early Christian communities.

Archaeological finds, including Roman coins and Christian artefacts, provide evidence of trade links with the Roman provinces of Britain and Gaul, through which Christian ideas also found their way to Ireland.

These early contacts prepared the ground for later systematic missionary work. The first Christian settlements were established in the coastal regions of south-east Ireland in particular, through which the faith was able to spread further into the country.

Saint Patrick – legend and historical facts

Saint Patrick, whose life is dated between the late 4th and mid 5th century, shaped the Christianisation of Ireland like no other personality. The son of a Romano-British family, he was abducted by Irish raiders as a teenager and spent six years as a slave in Ireland before he managed to escape.

After his religious training, he returned as a missionary, driven by a vision that called him to convert Ireland. His two surviving writings, the ‘Confessio’ and the ‘Letter to Coroticus’, provide important insights into his life and work, whereby facts and myths tend to blur together.

The best-known legend, the expulsion of the snakes from Ireland, is a symbolic representation of the overcoming of paganism. Patricks knew and respected Irish culture and tradition and knew how to use it skilfully by combining Celtic and Christian elements of faith. He also understood that he first had to convince the local rulers in order to be able to involve the population later on.

The missionary strategies of Saint Patrick

Patrick’s missionary work in Ireland was therefore remarkably strategic. He was not a blind zealot, but knew how to pick people up where they came from and lead them to where he saw the right path – with sensitivity and yet in a planned manner.

Instead of destroying pagan places of worship, he often rededicated them as Christian shrines and integrated existing feast days into the Christian calendar.

The most famous example is his use of the shamrock to explain the Trinity, through which he vividly conveyed complex theological concepts. The three-leaf clover still plays a major role today as a symbol of Ireland.

He first converted the tribal princes and then found it easier to convert the clans one by one.

Patrick established a system of local churches that were orientated towards the existing political structures and trained a native clergy. His missionary strategy took into account the strong role of women in Celtic society, which was reflected in the founding of women’s monasteries and the importance of female saints.

The Irish monastery system

The Irish monastic system developed into a unique form of monastic life that differed significantly from continental models.

The monasteries often developed as large settlements that included workshops, schools and farms in addition to the religious buildings.

Unlike in continental monasteries, the structure was less hierarchical and the abbots often had more authority than the bishops. Ecclesiastical power was therefore less centralised and distributed among more heads and decision-makers, much as secular power was in Irish clan structures. The monasteries functioned as centres of education, art and business, with many of them growing into veritable small towns.

A special feature was the system of ‘sea friendship’ (anamchara), in which spiritual mentors played an important role in personal development. The strict asceticism practised by many Irish monks became a model for European monasticism.

Significant early monastic foundations

The early Irish monastic foundations developed into important centres of spirituality, education and culture.

Clonmacnoise, founded by St. Ciarán in the 6th century on the banks of the River Shannon, became one of Ireland’s most important centres of learning and at times was home to up to 2000 monks. You can find my article on Clonmacnoise here: https://ireland-insider.com/clonmacnoise-monastic-site-a-treasure-at-the-river-shannon/.

Glendalough, the ‘valley of the two lakes’, founded by St Kevin, developed into a veritable monastic town with characteristic architecture, including its famous round tower. Read also my article: https://ireland-insider.com/glendalough-monastic-city-a-top-attraction-in-irelands-ancient-east/.

The monastery of Clonard under St Finnian became known as the ‘Teacher of the Saints of Ireland’ and trained the so-called ‘Twelve Apostles of Ireland’, who in turn founded other important monasteries.

Durrow and Kells, both associated with Columban, became important centres of book illumination.

These monasteries also took on important economic and social functions in their region and developed into hubs of an extensive network of monastic communities.

Irish written culture

The development of Irish writing culture represents one of the most significant contributions of the early Irish church to European cultural history. The monks developed a characteristic style of writing, the ‘insular script’, which was characterised by its particular clarity and artistic design.

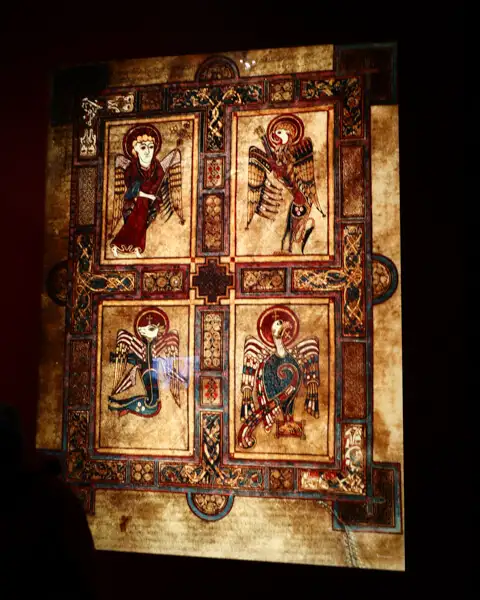

Masterpieces of book illumination such as the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow and the Book of Armagh were created in the scriptoria of the monasteries. The scribes not only preserved Christian texts, but also recorded ancient Irish literature and mythology, thus preserving much of the pre-Christian cultural heritage.

Today you can admire the ornate Book of Kells in Trinity College in Dublin. It is one of Ireland’s most important cultural treasures. See my article on this: https://ireland-insider.com/dublin-trinity-college/.

The Irish monks also developed innovative techniques for parchment production and bookbinding. By using the vernacular alongside Latin, they contributed significantly to the development of the Irish literary language.

Peregrinatio pro Christo

The ‘Peregrinatio pro Christo’, the voluntary pilgrimage for the sake of Christ, became a characteristic feature of Irish monasticism. Inspired by the ascetic ideal of leaving their homeland, numerous Irish monks set off on pilgrimages across Europe.

The Irish travelling monks brought with them not only their spiritual practices, but also their scholarship, their art and their manuscripts.

They played an important role in the Christianisation and cultural development of Europe during the ‘dark centuries’ following the collapse of the Roman Empire. Their mobility contributed to the spread of knowledge and the networking of the early medieval monastic landscape.

It can therefore be said that the Christian faith was first imported from the continent to Ireland, where it grew and flourished before being exported back to the continent. And this happened in the early Middle Ages, when travelling was extremely arduous and dangerous – impressive, isn’t it?

Columban the Younger and the Iro-Scottish mission

Columban the Younger (ca. 543-615) epitomises the spirit of the Irish wandering monks like no other. After his training in Bangor, he travelled to the continent with twelve companions, where he founded several influential monasteries.

His strict interpretation of the rules and his uncompromising zeal for reform repeatedly brought him into conflict with secular and ecclesiastical authorities. Nevertheless, or perhaps precisely because of this, his work had a lasting influence on the development of European monasticism.

The monasteries he founded – Luxeuil, Fontaines and Annegray in Burgundy and Bobbio in northern Italy – became important centres of Christianisation and education. His monastic rule, which was later partially integrated into the Benedictine rule, demonstrates the characteristic rigour and high intellectual standards of Irish monasticism.

The role of women

Women played a stronger role in Celtic culture than in Roman-influenced Christianity. As Irish Christianity combined Celtic and Christian elements, the position of women in the early Irish church was much stronger than on the continent.

The most prominent representative of the Christian faith was St Brigid of Kildare. St Brigid of Kildare (also: Brighid, Bride, Bridget; ca. 451-523) is Ireland’s most important saint alongside Patrick. She was probably born in Faughart near Dundalk, according to legend as the daughter of a noble Druid and a Christian slave. This ancestry already symbolises the fusion of Celtic and Christian traditions, which was also reflected in her work.

Around 470, Brigid founded the monastery of Kildare, which developed into the most important women’s monastery in Ireland. It was conceived as a double monastery in which male and female communities lived under the leadership of the abbess. Brigid thus established a model that became influential for the Irish church. The abbess of Kildare had a status comparable to that of a bishop.

Of particular interest is the overlapping of her person with the Celtic goddess Brigid, who was responsible for poetry, blacksmithing and healing. Many attributes of the goddess were transferred to the saint, such as the sacred fire – an eternal fire was maintained in Kildare until the Reformation, which was tended by nineteen nuns.

However, Brigid was by no means the only Irish priestess to found monasteries, as St Faithlinn, St Ita, Cairech Dergain and Gobnait also founded monasteries such as Clonburren, Killeedy and Ballyvourney.

Brigid’s legacy continues to this day:

Her feast day (1 February) coincides with the Celtic Imbolc festival and is still celebrated today

The Brigid cross, woven from rushes, is an important symbol of Irish identity

Numerous springs and wells are dedicated to her and are the destination of pilgrimages

Her name is a common female name in Ireland

In recent times, her feast day has been declared a public holiday in Ireland

This rich heritage of women’s monasteries, and of St Brigid in particular, shows the exceptional position that women held in the early Irish church – a position that had no parallel in continental Europe.

Fusion of Celtic and Christian culture

The fusion of Celtic and Christian traditions led to a unique form of Christianity in Ireland. Ancient Celtic symbols such as the triskele were imbued with Christian meaning, while pre-Christian festivals such as Imbolc merged with Christian saints’ feasts.

The characteristic high crosses combine Celtic ornamentation with Christian iconography and served as ‘bibles in stone’ for the communication of biblical stories.

A distinctive style developed in art that combined spiralling Celtic patterns with Christian motifs.

In the Book of Kells you will even find skilfully painted saints depicted alongside Celtic mythical creatures.

Irish saint worship retained elements of Celtic mythology, and many sacred sites retained their spiritual significance under a Christian guise. This cultural synthesis was also evident in literature, where Christian themes were combined with traditional narrative forms.

Monastery education system

The Irish monasteries developed a sophisticated education system that earned Ireland the reputation as the ‘island of saints and scholars’.

In addition to theological studies, the curriculum also included classical literature, grammar, rhetoric, astronomy and computus (calendar calculation). Knowledge of Latin and Greek was cultivated, while at the same time the Irish language was developed as a literary language.

The monastic schools attracted students from all over Europe and contributed to the preservation of classical texts. Education followed a tiered system that accepted both monastic and secular students, such as the sons of noble families from the continent.

The Viking invasions and their effects

The Viking invasions that began in the late 8th century posed a massive challenge to the Irish church. Many monasteries were plundered and destroyed, valuable manuscripts were lost and the established structures were shaken. The threat led to the construction of characteristic round towers, which served as refuges and treasuries.

However, the Vikings later also contributed to the urbanisation of Ireland by founding trading towns such as Dublin, Limerick, Waterford and Wexford. Read also my article on the Viking city of Waterford: https://ireland-insider.com/waterford-and-the-vikings/.

The monasteries adapted by hiding their treasures or moving them to the mainland.

After the Christianisation of the Vikings, there was a cultural fusion which is reflected in Irish-Nordic art.

High crosses and religious architecture

Irish sacred architecture developed characteristic forms that still characterise the landscape today. The monumental high crosses, often up to 6 metres high, artfully combined biblical scenes with Celtic ornaments and served as ‘Bibles in stone’ for conveying Christian stories.

The early church buildings were initially made of wood, later of stone, and were characterised by their simple, rectangular shape. The striking round towers, which were built from the 9th century onwards, served both as bell towers and as a refuge in the event of raids.

Particularly noteworthy are the ‘beehive huts’ (clochans), which served as hermitages and feature a unique stone construction technique without mortar. The architectural development reflects the transition from an eremitic to a cenobitic way of life. Read also my article on the remarkable stone houses of Dingle: https://ireland-insider.com/the-ancient-stone-houses-of-dingle/.

The 12th century reforms

The ecclesiastical reform of the 12th century marked a profound change in Irish church organisation. The synods of Rathbreasail (1111) and Kells-Mellifont (1152) led to the introduction of a continental-style diocesan structure and the establishment of four archbishoprics.

The traditional monastic dioceses were replaced by territorial bishoprics, and continental orders such as the Cistercians established themselves in Ireland. These reforms signalled the end of many traditional Irish church practices and led to greater integration into the pan-European church structure.

The old monastic families became less important, while new monasteries modelled on continental ones were built. Despite these changes, many local traditions were preserved.

However, these reforms were not adopted in Ireland entirely voluntarily, but were imposed on the Irish Church during the Anglo-Norman invasion. The Irish Church was too independent for the Pope in Rome and so he took the opportunity to bring it under control. See also my article on the Norman Invasion: https://ireland-insider.com/the-norman-invasion-of-ireland/ .

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, which swept across the country from England and was accompanied by another wave of invasions, also led to massive changes: Many Irish monasteries wonder closed and destroyed and Protestant churches were built all over the country. But that might be a topic in its own right…

Conclusion

The legacy of the early Irish church is still alive and visible today. The many surviving monastic ruins, high crosses and round towers are not only important tourist attractions, but also evidence of a unique cultural synthesis.

Traditional pilgrimage routes such as Croagh Patrick continue to be walked, and ancient saints’ cults live on in a modified form. Artistic traditions, especially Celtic ornaments and cross symbols, have become important elements of Irish identity.

Early Irish church history plays an important role in Ireland’s cultural identity and has had a lasting impact on the country’s religious landscape.

I myself am not an actively practising Christian, but I too am fascinated by the old monastery ruins that I come across time and again on my travels in Ireland in beautiful scenic locations.

Perhaps it’s the magic of the place, as Christian monasteries and churches were often built on sacred sites of the Gaelic Celts. The Gaels were very close to nature and had a special feeling for special places in nature.

Perhaps it is the striking round towers and the Celtic crosses with their skilful stone carvings and perhaps it is the Celtic ornaments and motifs that can always be found there.

Perhaps it is also the history of the island, which has developed so impressively away from the continent – and perhaps all of this together!

If you go to Ireland, you might feel the same way I do – have fun!

More interesting articles for you

Ireland’s history from the Stone Age to the Modern Age – an overview

Burrishoole Abbey – a pretty ruin at Clew Bay

Romantic Tintern Abbey

Monasterboice – celtic crosses and a roundtower

Kylemore Abbey in Connemara

Picture credits cover picture: Chapel at Mamore Gap, photo: Ulrich Knüppel-Gertberg (https://irland-insider.de, https://ireland-insider.com)